I think we’ve all been there before – you log on to a server remotely via RDP, and do the needful – but don’t immediately log off. But then you get distracted by a phone call, an email, a chat, or a good old-fashioned physical interaction with another human being. So when it comes time clock out for the night, you shut down your computer or log off. Or maybe you’ve been working on a laptop and your VPN got interrupted. The result is the same – previously active RDP sessions are automatically disconnected. Or maybe one (not you, of course) purposely disconnects their session so that the next login process is faster.

Well whatever may be the reason, a key issue with disconnected RDP sessions is that, by default, they remain connected indefinitely until the server gets rebooted, you login again (because you forgot to do something?), or a coworker notices the offense and politely requests you log off.

At this point you’re probably thinking “OK, yes, but who really cares“? With all the serious stuff that’s going on around you, you’re probably wondering why the heck you suddenly need to worry about disconnected RDP sessions? Well, disconnected RDP sessions can be problematic for a number of reasons:

Potential Issues

Confusion

It can be confusing when you’re logging on to a server and notice that another user is logged on, even if it’s just a disconnected session. Are they doing important stuff? Can the other user by logged off? Or you’re trying to reboot a server, but the infamous “Other users are currently logged on … ” message pops up. Assuming you’re polite, you’ll reach out to the disconnected fellow to ensure that the user isn’t running any important apps. In short, it’s a pain. And we all have enough pain as it is, do we not?

Security

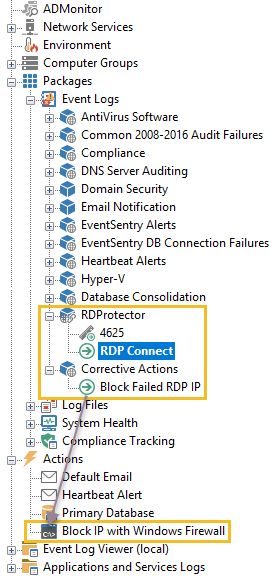

So this is the fun one and, I admit, the real reason for this blog post (no, it was not the confusion). Turns out that any local administrator has the ability to hijack any disconnected session on the server he or she is an administrator on. And while this doesn’t sound like a huge problem at first (if the user is already an admin, then he can do anything blah blah), there is a very specific scenario where this is a significant security risk. Being an admin on a machine is a great privilege, but hardly the key to the kingdom. If a domain admin (or even worse, an Enterprise Admin!) however logs on to the same host and disconnects their session, then the local admin can promote himself/herself to domain admin at no cost (EventSentry would of course detect this) by simply taking over the disconnected session. The process involves only a handful of commands, one of which is creating a temporary service (EventSentry would detect this also).

Resource Consumption

Processes from disconnected sessions do continue to run and consume some processing power, which can be an issue in environments with limited computing power or cloud environments where you pay for CPU time. It’s unlikely to have a large impact but it could add up for larger deployments.

I’m hoping that we can (almost) all agree now that disconnected sessions have a number of drawbacks, so let’s move on to ways to address this.

Solutions

User Education

While there are ways to forcefully log off idle users (see below), I think it’s important to make your admins aware that disconnected sessions pose a security risk, but also communicate to your users in general that disconnected sessions should be avoided when necessary. While this won’t solve the problem entirely, it will hopefully get some of your users to be more aware.

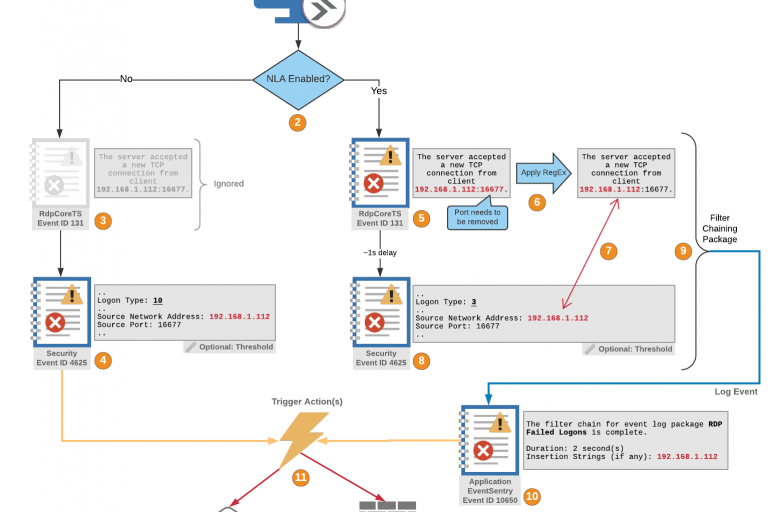

Notifications

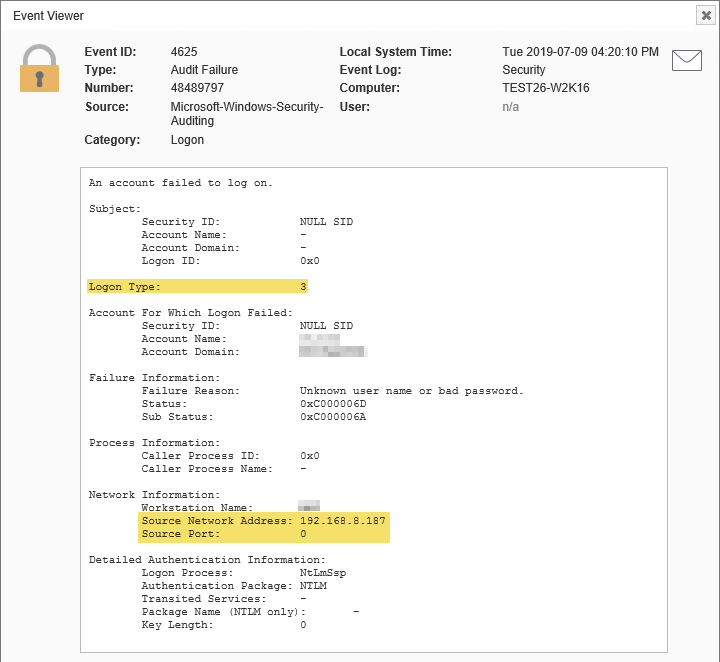

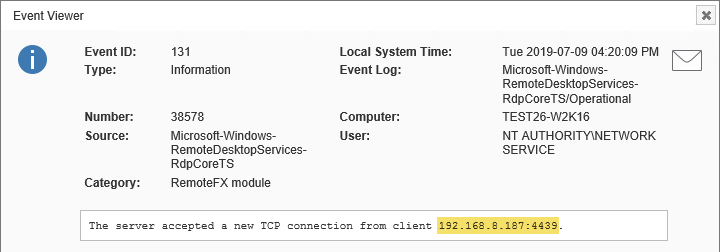

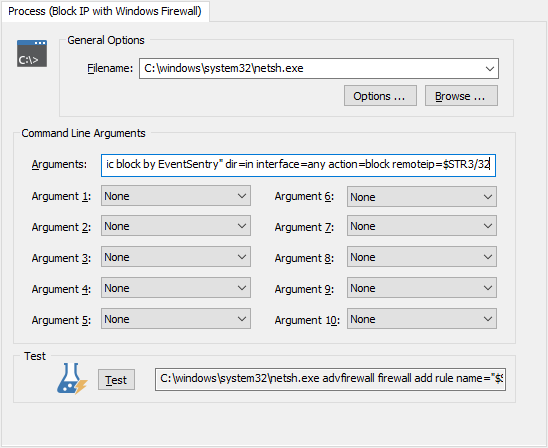

EventSentry users can utilize filter timers to get notified when a user has been logged on to a server too long. Those not familiar with filter timers can learn more about them here. In short, filter timers work with events that are usually logged in pairs – such as a process start/process end, logon/logoff, service stop/service start etc – and can notify you when such an event pair is incomplete. For example, a logon is recorded but not followed by a logoff within a certain amount of time (the time period is configurable).

So in this scenario, a user’s logon event would start a filter timer that essentially puts the original event on hold. It won’t forward it to a notification just yet – only if the timer expires and no subsequent event has deleted the timer. A later logoff event (that is linked to the logon event via some property of the event like a login ID) would end the filter timer. If the logoff event does not happen (or happen too late), EventSentry will release the pending (logon) event and can send a notification to let either the team or the user know (if the login pattern matches email addresses) that the filter time has expired.

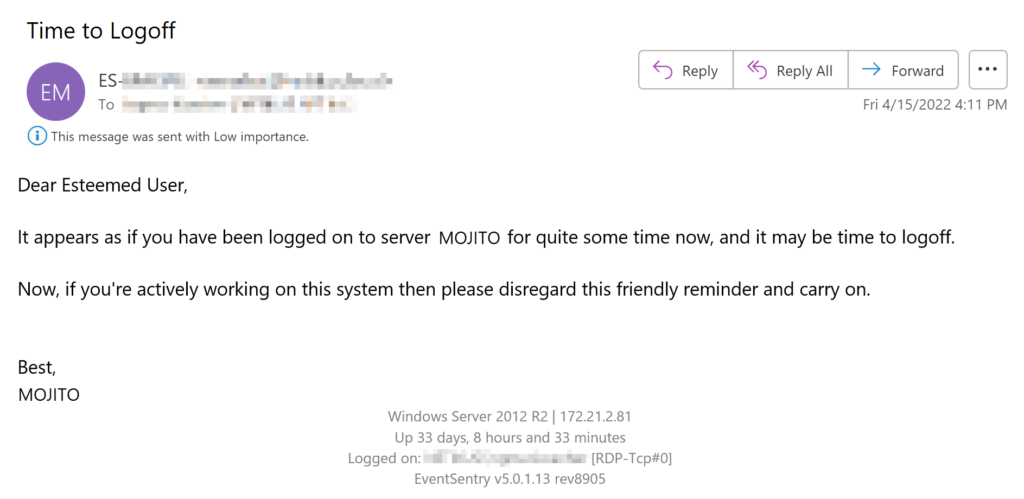

BONUS: If the Windows username can be matched to an email address (e.g. username is john.doe and the email address is john.doe@mycorp.com), then EventSentry can even send an email directly to the user (opposed to a generic email) reminding them to log off. Even better, the email can be customized and provide specific instructions. See KB 465 for instructions on how to configure this in EventSentry. The screenshot below shows such a customized email.

Disclaimer: This method doesn’t necessarily distinguish between users who are logged on and users who have disconnected sessions. It detects that a user has had a Windows session active for an extended time period. In most cases this should work reasonably well to detect disconnected sessions as well. especially with longer timer periods (since most users don’t need to be logged on to a server for many hours).

Forcibly logging off disconnected sessions

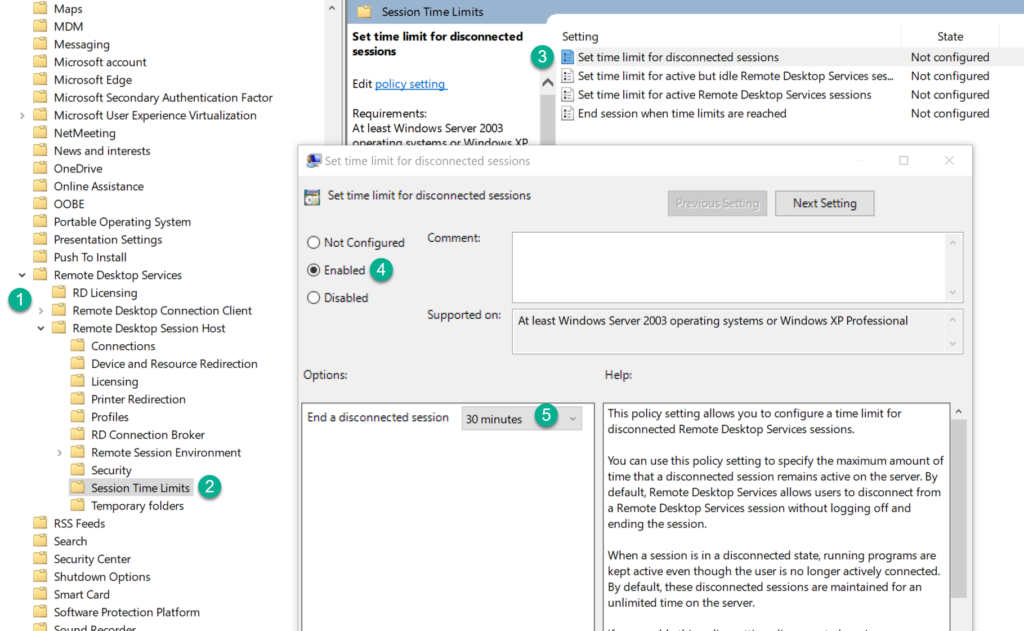

When you tried your best the nice way using education and emails and it’s just not working, well, then it turns out that Windows allows you to use the nuclear button – logging off disconnected user sessions after a certain time. Since this can be configured via group policy, implementing this is fairly easy. Simply create a new group policy and assign it to appropriate OU(s) and configure the following setting:

Local Computer Policy

|-- Computer Configuration

|-- Administrative Templates

|-- Windows Components

|-- Remote Desktop Services

|-- Remote Desktop Session Host

|-- Session Time Limits

Then simply enable the option and configure an appropriate time limit. The available timeout options are actually quite useful and range from 1 minute (which pretty much converts a disconnect with a logoff) all the way up to 5 days (which is better than nothing I suppose, but why even bother at that point?). What option you select here largely depends on how concerned you are about resource usage and sessions being hijacked. I personally would recommend a lower end of 30 minutes up to 8 hours at the maximum.

Validating RDP settings with EventSentry Validation Scripts

EventSentry includes two validation scripts that validate whether RDP session timeouts are enabled:

1. Disconnect sessions after user is idle for X minutes

2. Logoff disconnected sessions after X minutes

Conclusion

Disconnected RDP sessions aren’t an immediate security risk, since they require an intruder to somehow gain admin rights on a domain member machine first. Sophisticated attacks however rarely involve just one step, but usually take advantage of multiple vulnerabilities and exploits. Since there are few to no downsides to notifying or even logging off users after a certain amount of time, I would recommend to follow the recommendations outlined in this blog post.