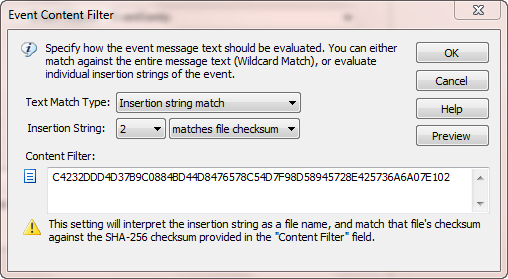

If you’ve ever wrote code to log to the Windows event log before (e.g. through Perl, Python, …), then you might have run into a similar problem that I described in an earlier post: Either the events don’t look correctly in the event log, you are restricted to a small range of event ids (as is the case with eventcreate.exe) or you cannot utilize insertion strings.

In this blog post I’ll be showing you how to build a custom event message DLL, and we’ll go about from the beginning to the end. We’ll start with creating the DLL using Visual Studio (Express) and finish up with some example scripts, including Perl of course, to utilize the DLL and log elegantly to the event log.

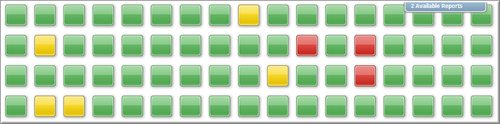

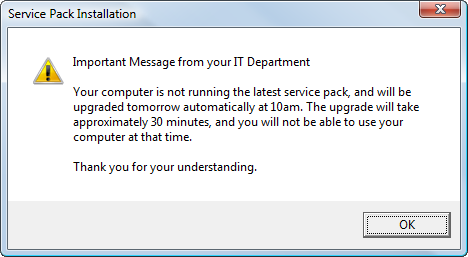

Let’s say you are running custom scripts on a regular basis in your network – maybe with Perl, Python, Ruby etc. Your tasks, binary as they are, usually do one of two things: They run successfully, or they fail. To make troubleshooting easier, you want to log any results to the event log – in a clean manner. Maybe you even have sysadmins in other countries and want to give them the ability to translate standard error messages. Logging to the event log has a number of benefits: It gives you a centralized record of your tasks, allows for translation, and gives you the ability to respond to errors immediately (well, I’m of course assuming you are using an event log monitoring solution such as EventSentry). Sounds interesting? Read on!

Yes, you can do all this, and impress your peers, by creating your own event message file. And what’s even better, is that you can do so using all free tools. Once you have your very own event message file, you can utilize it from any application that logs to the event log, be it a PowerShell/perl/python/… script or a C/C++/C#/… application.

To create an event message file, you need two applications:

The reason you need the platform SDK, is because Visual Studio Express does not ship with the Message Compiler, mc.exe, for some reason. The message file compiler is essential, as without it there will be no event message file unfortunately. When installing the platform SDK, you can deselect all options except for “Developer Tools -> Windows Development Tools -> Win32 Development Tools” if you want to conserve space. This is the only essential component of the SDK that’s needed.

An event message file is essentially a specific type of resource that can be embedded in either a DLL file or executable. In EventSentry, we originally embedded the message file resources in a separate DLL, but eventually moved it into the executable, mostly for cleaner and easier deployment. We’ll probably go back to a separate message DLL again in the future, mostly because processes (e.g. the Windows Event Viewer) can lock the event message file (the executable in our case), making it difficult to update the file.

Since embedding an event message file in a DLL is more flexible and significantly easier to accomplish, I’ll be covering this scenario here. The DLL won’t actually contain any executable code, it will simply serve as a container for the event definitions that will be stored inside the .dll file. While it may sound a little bit involved to build a DLL just for the purpose of having an event message file (especially to non-developers), you will see that it is actually surprisingly easy. There is absolutely no C/C++ coding required, and I also made a sample project available for download, which has everything setup and ready to go.

In a nutshell, the basic steps of creating an event message file are as follows:

1. Create a message file (e.g. messagefile.mc)

2. Convert the message file into a DLL, using mc.exe, rc.exe and link.exe

Once we have the message file, we will also need to register the event message file in the registry, and associate it with an event source. Keep in mind that the event source is not hard-coded into the message file itself, and in theory a single event message file could be associated with multiple event sources (as is the case with many event sources from Windows).

So let’s start by creating a working folder for the project, and I will call it “myapp_msgfile”. Inside that directory we’ll create the message file, let’s call it myapp_msgfile.mc. This file is a simple text file, and you can edit it with your favorite text editor (such as Ultraedit, Notepad2 or Notepad++).

The file with the .mc extension is the main message file that we’ll be editing – here we define our event ids, categories and so forth. Below is an example, based on the scenario from before. Explanations are shown inline.

MessageIdTypedef=WORD

LanguageNames=(

English=0x409:MSG00409

German=0x407:MSG00407

)

Here we define which languages we support, and by which files these languages will be backed. You will have to look up the language id for other languages if you plan on supporting more, and you can remove German if you only plan on supporting English.

MessageId=1

SymbolicName=MYTOOL_CATEGORY_GENERAL

Language=English

Tasks

.

Language=German

Jobs

.

Our first event id, #1, will be used for categories. Categories work in the exact same way as event ids. When we log an event to the event log and want to include a category, then we only log the number – 1 in this case.

MessageId=100

SymbolicName=TASK_OK

Language=English

Task %1 (%2) completed successfully.

.

Language=German

Job %1 (%2) war erfolgreich.

.

This is the first event description. The “MessageId” field specifies the event id, and the symbolic name is a descriptive and unique name for the event. The language specifies one of the supported languages, followed by the event message text. You end the event description with a single period – that period has to be the only character per line.

MessageId=101

SymbolicName=TASK_ERROR

Language=English

Task %1 (%2) failed to complete due to error “%3”.

.

Language=German

Job %1 (%2) konnte wegen Fehler “%3” nicht abgeschlossen werden.

.

MessageId=102

SymbolicName=TASK_INFO

Language=English

Task Information: %1

.

Language=German

Job Information: %1

.

Since we’re trying to create events for “custom task engine”, we need both success and failure events here. And voila, our event message file now has events 100 – 102, plus an id for a category.

So now that we have our events defined, we need to convert that into a DLL. The first step now is to use the message compiler, mc.exe, to create a .rc file as well as the .bin files. The message compiler will create a .bin file for every language that is defined in the mc file. Open the “Visual Studio Command Prompt (2010)” in order for the following commands to work:

mc.exe myapp_msgfile.mc

will create (for the .mc file depicted above):

myapp_msgfile.rc

msg00407.bin

msg00409.bin

With those files created, we can now create a .res (resource) file with the resource compiler rc.exe:

rc.exe /r myapp_msgfile.rc

which will create the

myapp_msgfile.res

file. The “/r” option instructs the resource compile to emit a .res file. Now we’re almost done, we’re going to let the linker do the rest of the work for us:

link -dll -noentry -out:myapp_msgfile.dll myapp_msgfile.res

The myapp_msgfile.res is the only input file to the linker, normally one would supply object (.obj) files to the linker to create a binary file. The “-noentry” option tells the linker that the DLL does not have an entry point, meaning that we do not need to supply a DllMain() function – thus the linker is satisfied even without any object files. This is of course desired, since we’re not looking to create a DLL that has any code or logic in it.

After running link.exe, we’ll end up with the long awaited myapp_msgfile.dll file.

The end. Well, almost. Our message file is at this point just a lone accumulation of zeros and ones, so we need to tell Windows that this is actually a message file for a particular event log and source. That’s done through the registry, as follows:

Open the registry editor regedit.exe. Be extremely careful here, the registry editor is a powerful tool, and needs to be used responsibly :-).

All event message files are registered under the following key:

HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\eventlog

Under this key, you will find a key for every event log as well as subkeys for every registered event source. So in essence, the path to an event source looks like this:

HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\eventlog\EVENTLOG\EVENTSOURCE

I’m going to assume here that we are going to be logging to the application event log, so we’d need to create the following key:

HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\eventlog\Application\MyApp

In this key, we need to following values:

TypesSupported (REG_DWORD)

EventMessageFile (REG_EXPAND_SZ)

TypesSupported is usually 7, indicating that the application will log either Information, Warning or Error events (you get 7 if you OR 1[error], 2[warning] and 4[information] together).

EventMessageFile is the path to your message DLL. Since the type is REG_EXPAND_SZ, the path may contain environment variables.

If you plan on utilizing categories as well, which I highly recommend (and for which our message file is already setup), then you need two additional values:

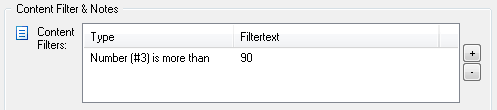

CategoryCount (REG_DWORD)

CategoryMessageFile (REG_EXPAND_SZ)

CategoryCount simply contains the total number of categories in your message file (1, in our case), and the CategoryMessageFile points to our message DLL. Make sure that your message file does not contain any sequence gaps, so if your CategoryCount is set to 10, then you need to have an entry for every id from 1 to 10 in the message file.

We could create separate message files for messages and categories, but that would be overkill for a small project like this.

Now that we have that fancy message DLL ready to go, we need to start logging. Below are some examples of how you can log to the event log with a scripting language. I’ll be covering Perl, Kix, and Python. Me being an old Perl fan and veteran, I’ll cover that first.

PERL

The nice thing about Perl is that you can take full advantage of insertion strings, so it can support event definitions containing more than one insertion string.

use strict;

use Win32::EventLog;

# Call this function to log an event

sub logMessage

{

my ($eventID, $eventType, @eventDetails) = @_;

my $evtHandle = Win32::EventLog->new(“Your Software Application”);

my %eventProperties;

# Category is optional, specify only if message file contains entries for categories

$eventProperties{Category} = 0;

$eventProperties{EventID} = $eventID;

$eventProperties{EventType} = $eventType;

$eventProperties{Strings} = join("\0", @eventDetails);

$evtHandle->Report(\%eventProperties);

$evtHandle->Close;

}

# This is what you would use in your scripts to log to the event log. The insertion strings

# are passed as an array, so even if you only have one string, you would need to pass it

# within brackets (“This is my message”) as the last parameter

logMessage(100, EVENTLOG_INFORMATION_TYPE, (“Database Backup”, “Monitoring Database”, “Complete”));

logMessage(102, EVENTLOG_INFORMATION_TYPE, (“Step 1/3 Complete”));

PYTHON

Python supports event logging very well too, including multiple insertion strings. See the sample code below:

import win32evtlogutil

import win32evtlog

# Here we define our event source and category, which we consider static throughout

# the application. You can change this if the category is different

eventDetails = {‘Source’: ‘MyApp’, # this is id from the message file

‘Category’: 1} # which was set aside for the category

# Call this function to log an event

def logMessage(eventID, eventType, message, eventDetails):

if type(message) == type(str()):

message = (message,)

win32evtlogutil.ReportEvent(eventDetails[‘Source’], eventID, eventDetails[‘Category’], eventType, tuple(message))

logMessage(100, win32evtlog.EVENTLOG_INFORMATION_TYPE, (“Database Backup”, “Monitoring Database”), eventDetails)

logMessage(102, win32evtlog.EVENTLOG_INFORMATION_TYPE, (“Step 1/3 complete”), eventDetails)

KIXTART

The pro: Logging to the event log using KiXtart is so easy it’s almost scary. The con: It only supports message files that use one insertion string.

LOGEVENT(4, 102, "Database Backup", "", "MyApp")